In the world of surfing, wave height is not just a casual observation—it is a fundamental element that shapes the entire experience. Whether you’re a seasoned big-wave rider charging giants at Jaws or a beginner catching your first ankle-biters, understanding how to measure wave height is key to evaluating risk, choosing the right equipment, planning your sessions, and interpreting forecasts.

But here’s the twist: wave height in surfing is not measured the same way everywhere. It’s a subject of debate, regional variation, and cultural nuance. Surfers in Hawaii might look at a 12-foot face and call it a “6-foot wave,” while someone from Australia or California might describe the same wave as 12 feet. This inconsistency has led to confusion, humorous banter, and the need for standardized approaches.

This article dives deep into how wave height is measured in surfing—covering traditional and modern methods, regional differences, measurement tools, forecasting practices, and why consistency is important for safety and sport progression.

The Two Main Approaches: Wave Face vs. Hawaiian Scale

Wave Face Height (Face Measurement)

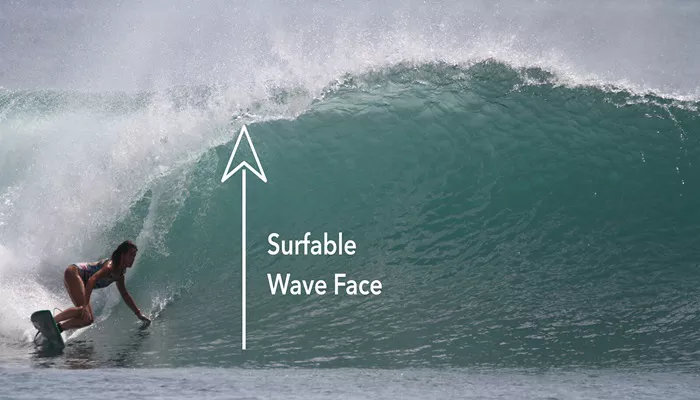

The most straightforward way to measure a wave is by looking at the wave face—the vertical distance from the trough (bottom) of the wave to the crest (top) of the breaking part of the wave. This method is commonly used by:

- International surf competitions (e.g., WSL – World Surf League)

- Surf forecast services like Surfline and Magicseaweed

- Surfers from California, Australia, Europe, and most of the world

For example, if a wave has a 10-foot vertical face, it’s called a “10-foot wave.” This system is intuitive and correlates well with the size of wave a surfer must navigate.

The Hawaiian Scale

The Hawaiian scale takes a more conservative approach. A wave that is 10 feet on the face may be called a “5-foot wave” in Hawaii. This tradition dates back to the early days of big-wave surfing in the islands, where wave size was estimated based on the back of the wave, which appears smaller than the front.

Reasons behind the Hawaiian scale:

- Rooted in local surf culture and norms

- Aimed at maintaining modesty and humility in surf reports

- Provides a unique identity for Hawaiian surf communication

In essence, the Hawaiian scale often reads about half the size of the face measurement. However, the conversion isn’t always exactly 50%—it’s more of a general guideline.

Scientific Methods of Measuring Wave Height

While surfers often rely on visual estimates, science and technology have introduced precise instruments and methods:

1. Buoy Data

Oceanographic buoys, managed by entities like NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), are positioned offshore to record various swell characteristics. Key parameters include:

Significant Wave Height (SWH): This is the average height of the highest one-third of waves over a certain time period.

Peak Wave Period: The time between waves, affecting their power.

Wave Direction: Where the swell is coming from.

SWH is commonly used in marine forecasts and surf predictions but may underestimate the size of the largest individual waves, which can be 1.5 to 2 times higher than the SWH value.

2. LIDAR and Radar Systems

High-tech systems like LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) and radar are used to monitor nearshore and open-ocean waves:

- Provide real-time wave profiles

- Extremely accurate and useful for scientific analysis and coastal engineering

- Still relatively rare in commercial surf applications

3. Video and Photo Analysis

In surf competitions and big-wave events, footage is often analyzed post-session:

Judges estimate height using frame-by-frame analysis.

Reference objects (like the surfer) are used to scale wave size.

Advanced AI systems are now being developed to automate this process.

Human Perception and Its Challenges

Eyeballing Waves: Subjective but Traditional

Many surfers still use the “eyeball method,” especially in lineups without access to data. However, estimating wave height by eye comes with challenges:

Angle of view: Waves look smaller from the beach than in the water

Perspective distortion: A surfer duck-diving may see a wave as larger than it actually is

Wave type: A barreling wave may appear steeper and taller, influencing the estimate

The Surfer-as-Scale Method

This method uses the height of a surfer (typically assumed at around 6 feet) to estimate the wave face. If a wave face is roughly double the surfer’s height, it’s likely in the 10-12 foot range.

While imprecise, it’s a helpful method for photographers, judges, and fellow surfers comparing wave sizes visually.

Why Consistency in Measurement Matters

1. Safety and Risk Assessment

Misjudging wave height can lead to life-threatening situations. A surfer expecting 6-foot waves (on the face) but encountering a “Hawaiian 6-footer” (face 12-15 feet) might be dangerously underprepared.

2. Competition Scoring and Records

In competitive surfing, accurate wave height measurement is critical for:

- Establishing fairness across heats

- Documenting world record waves (e.g., Guinness World Records)

- Assessing performance on big-wave platforms (e.g., Nazaré or Mavericks)

3. Surf Forecast Communication

Forecasting services strive to bridge the gap between data and human interpretation. They typically provide both:

- Wave face height (in feet or meters)

- Descriptive terms: Such as “chest-high,” “overhead,” “double overhead”

This ensures clarity for surfers of different experience levels.

Descriptive Wave Size Terminology

In addition to numeric values, surfers often use descriptive terms.

| Term | Approximate Wave Face Height |

| Knee-high | 1-2 feet |

| Waist-high | 2-3 feet |

| Chest-high | 3-4 feet |

| Shoulder-high | 4-5 feet |

| Head-high | 5-6 feet |

| Overhead | 6-8 feet |

| Double overhead | 10-12 feet |

| Triple overhead | 15-18 feet |

These terms provide a quick reference but are inherently vague—what’s “head-high” to one surfer could vary depending on personal height and viewing angle.

Wave Size in Big Wave Surfing

Defining a “Big Wave”

In the world of big-wave surfing, wave height becomes even more critical. A wave is typically classified as “big” if:

- It exceeds 20 feet (face height)

- Requires tow-in techniques or special big-wave boards (guns)

- Poses serious risks due to hold-downs, currents, and impact zones

Official Record Standards

Organizations like the World Surf League (WSL) and Guinness World Records use:

- Video footage and photography

- Digital wave analysis software

- Surfer’s height and equipment as reference points

For example, Maya Gabeira’s record wave at Nazaré (73.5 feet) was verified using professional methods including image scaling and topographical analysis.

Regional Differences and Cultural Norms

Surf culture is rich in tradition, and wave measurement is no exception. Here’s a look at how different regions interpret wave height:

| Region | Typical Measurement Style |

| Hawaii | Hawaiian scale (back of wave) |

| California | Wave face measurement |

| Australia | Mixed usage; face preferred |

| Europe | Face measurement |

| Brazil | Face measurement |

Understanding local norms helps prevent confusion in conversations or when reading forecasts while traveling.

Conclusion

So, how do you measure wave height in surfing? The answer is: it depends. Whether you prefer the face measurement, the Hawaiian scale, or scientific instruments, what matters most is consistency and context.

For practical purposes, wave face height is the most universally understandable and useful—especially when communicating with surfers from different backgrounds or interpreting surf forecasts. Scientific tools and visual analysis continue to improve, helping us refine our understanding of ocean swell behavior.

Next time you paddle out, whether you’re scoring glassy overheads or knee-high peelers, remember that every surfer sees waves a little differently. But with a little knowledge and the right perspective, you’ll always be able to read the sea with confidence.